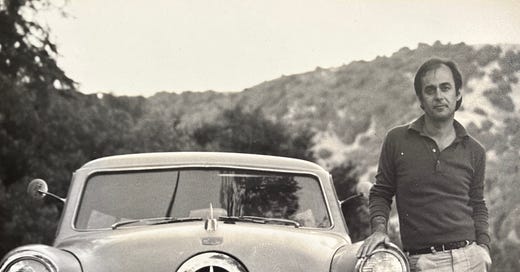

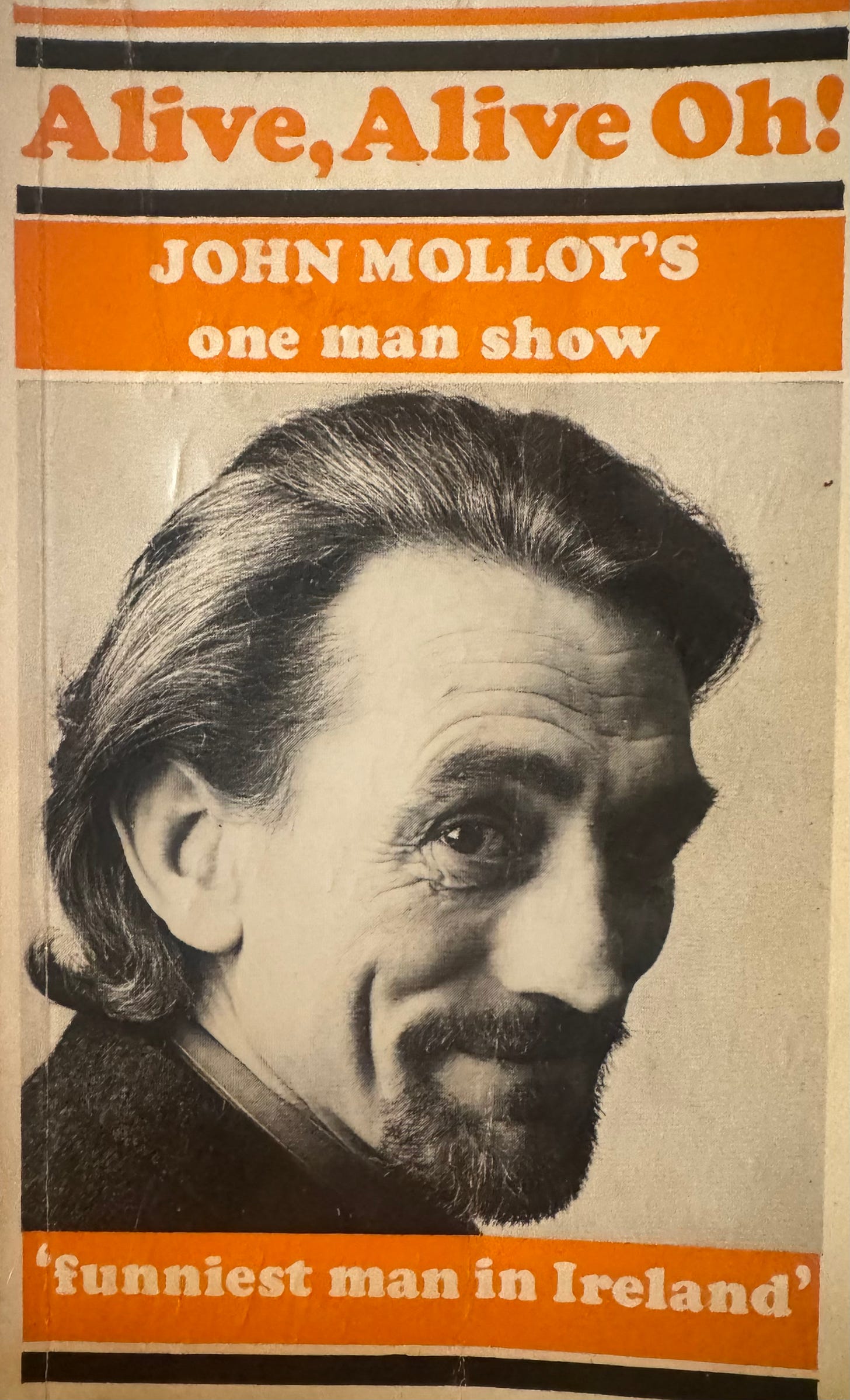

In the spring of 1977, my car was hit at an intersection. I had recently restored my vintage Studebaker Starlight coupe, and this accident broke the spell of my enchantment with the car. Still drivable, I did not have it repaired. Instead, I spent the insurance money on a ticket to Ireland.

My paternal grandparents were from County Cavan, Ireland. Somehow, they made their way to Massachusetts. My father was born here. Tragedy struck the family when his father, who took care of horses for his livelihood, was killed at work. My dad and his two brothers were taken out of school to earn money to support their mother and sisters. That is all I knew of my father’s family history.

(Farley with his Studebaker, Photograph by Jules Backus)

Growing up, I recall that when the Notre Dame football team was playing, my father had a radio blasting the game throughout the house. In the living room, the radio was on. A few steps away in the kitchen, another radio cheering the Fighting Irish blared on about yards gained and lost. This was not a big house, but my father wanted to make sure he wouldn’t miss any plays. He never went to Notre Dame, or any other school, for that matter, yet his love of his Irish heritage was deeply ingrained in his being.

“Being Irish, he had an abiding sense of tragedy, which sustained him through temporary periods of joy.” A quote by William Butler Yeats, who did not know my father, for certain. Or did he?

I landed in Ireland armed with a Super 8 sync-sound movie camera, with absolutely no idea what I was going to do. To my great surprise, the Dublin Folk Festival, a week-long celebration of traditional Irish music, was just beginning. I began to go to the pubs where the festival was taking place and, without permission, started recording. The great Christy Moore was the first musician I recorded. It’s hard to believe, but no one seemed to notice what I was doing.

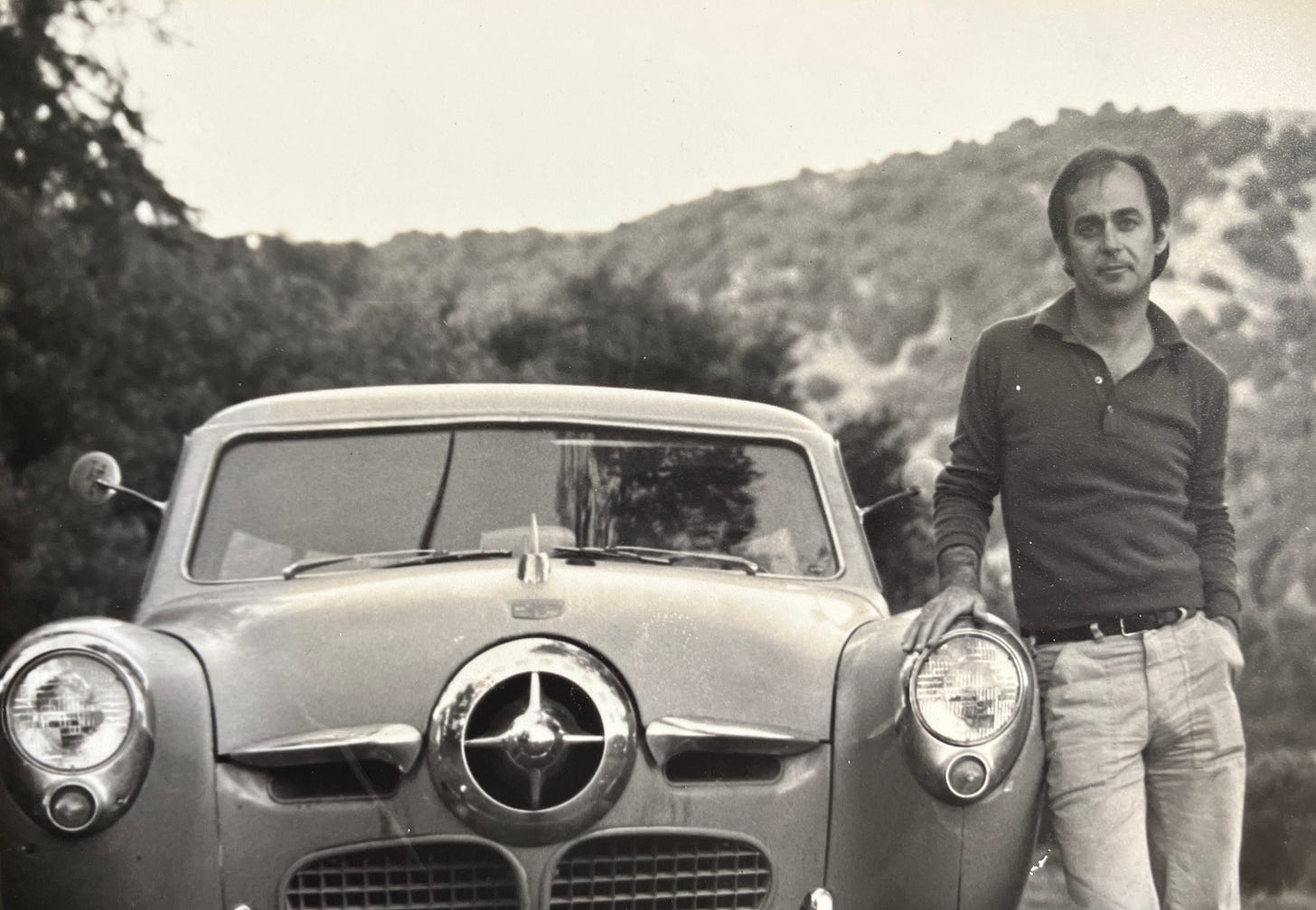

On my third day in Dublin, I was browsing in a bookstore when the clerk asked me where I was from. I said I lived in Berkeley, California. He started laughing. “I used to perform at the Berkeley Stage Company.” Over a pint of Guinness, he told me I must meet John Molloy, a well-regarded performer on the Dublin stage and the man who built the shelves the books I was perusing were sitting on. He said, “Molloy had just completed a run of his one-man show and was now facing an actor’s constant dilemma: unemployment. He added that Molloy was probably available.”

John Molloy was a slender, energetic man, constantly rolling and smoking cigarettes. He had an ingenious ability to poetically deliver a vivid portrait of his Irish perception of reality. When asked how he inherited such a talent, he said, “The Irish had been so poor for so long that all they could put into their mouths were words.” After a couple of days of long conversations, John Molloy agreed to help me with my film project.

(Published in the Republic of Ireland, photograph by Robert Dawson)

He told me a story about the 1916 Easter Rising, when the Irish rebelled against British rule. The British retaliated by bombing the General Post Office, which the rebels had taken over. Hundreds of people in the midst of the destruction were dislodged from their living quarters under the city. This population had never been seen before; they wore layers of ragged fur clothing to protect themselves from the elements. To the Dubliners, they looked prehistoric. He said that Samuel Beckett’s father, William, took young Samuel to view the chaos. The experience had a profound influence on his future writing. Mr. Molloy said many of the descendants of these underground people could still be seen living beneath the tunnels and waterways throughout Dublin. He offered to help me find them. With camera in hand, we toured around the city for a day where no tourist would dare to explore, all to no avail. After calling off the search and the exchange of a small amount of American currency, John agreed to allow me to film an excerpt of his show. John’s one-man show, Molloy, was captivating. His reminiscing about the Dublin of his youth and the adventures of a showman, as he called his profession, were witty and amazing.

Back in San Francisco, I suggested to my friend, theater director George Coates, founder of the San Francisco International Theater Festival, that he should consider inviting John Molloy to the festival. Through my enthusiasm, John was invited to stage his show for the 1981 season.

The San Francisco reviews for the Molloy show were outstanding, receiving raves in the local press. Ticket sales skyrocketed. The festival had a hit on its hands. The first thing Molloy did after receiving this public acclaim was to sell his return ticket back to Ireland. For the first time, I realized I had a bona fide rascal on my hands.

I regularly went out for coffee with John and his pal, university professor Kelley. John continued to tell stories of his mad, adventurous life in the theater. Many times, his stories were so funny that I could not stop laughing, literally falling over, unable to catch my breath. With my hands waving in the air, begging him to stop his storytelling, I was afraid I might die from a lack of oxygen. This did not dissuade him one bit, as he knew I would survive the ordeal.

I recall Br’er Rabbit being caught by Brother Bear and begging him, “Do whatever you want to do to me, but please, please don’t throw me into that briar patch.”*

And, of course, there was the shadow of Molloy’s past. It lingered not far below the surface of his personality, providing remembrances of mistakes made, which he could not quite put to rest. His inability to forgive himself plagued him and drove him into behaviors that nearly took his life.

To be continue……

*In spite of all the annoying thorns and brush this was where B’rer Rabbit lived and was completely comfortable in that environment.

William Farley©2025

Terrific stuff!! CAN’T WAIT FOR NEXT MOLLOY POST! Thanks Farley!