I received a commission to make a film about an eighty-two-year-old painter. Her subject matter was portraits of both famous and invisible individuals from the communities where she lived. She also had a passion for creating large canvases depicting catastrophes of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. During a break in her studio between setups, her husband, Harold Kozloff, came and sat beside me. Out of the blue, he shared three horrific stories about his combat experiences during World War II. The tone of his storytelling was unsettling, as there was an uncensored enthusiasm in his descriptions of killing Nazi soldiers. His hatred of Germans was palpable. I was struck silent—I had never heard anyone speak of war in such a manner. When I was called back on set for the next interview for the documentary about the painter (Harold's wife), I thanked him for his stories and returned to work.

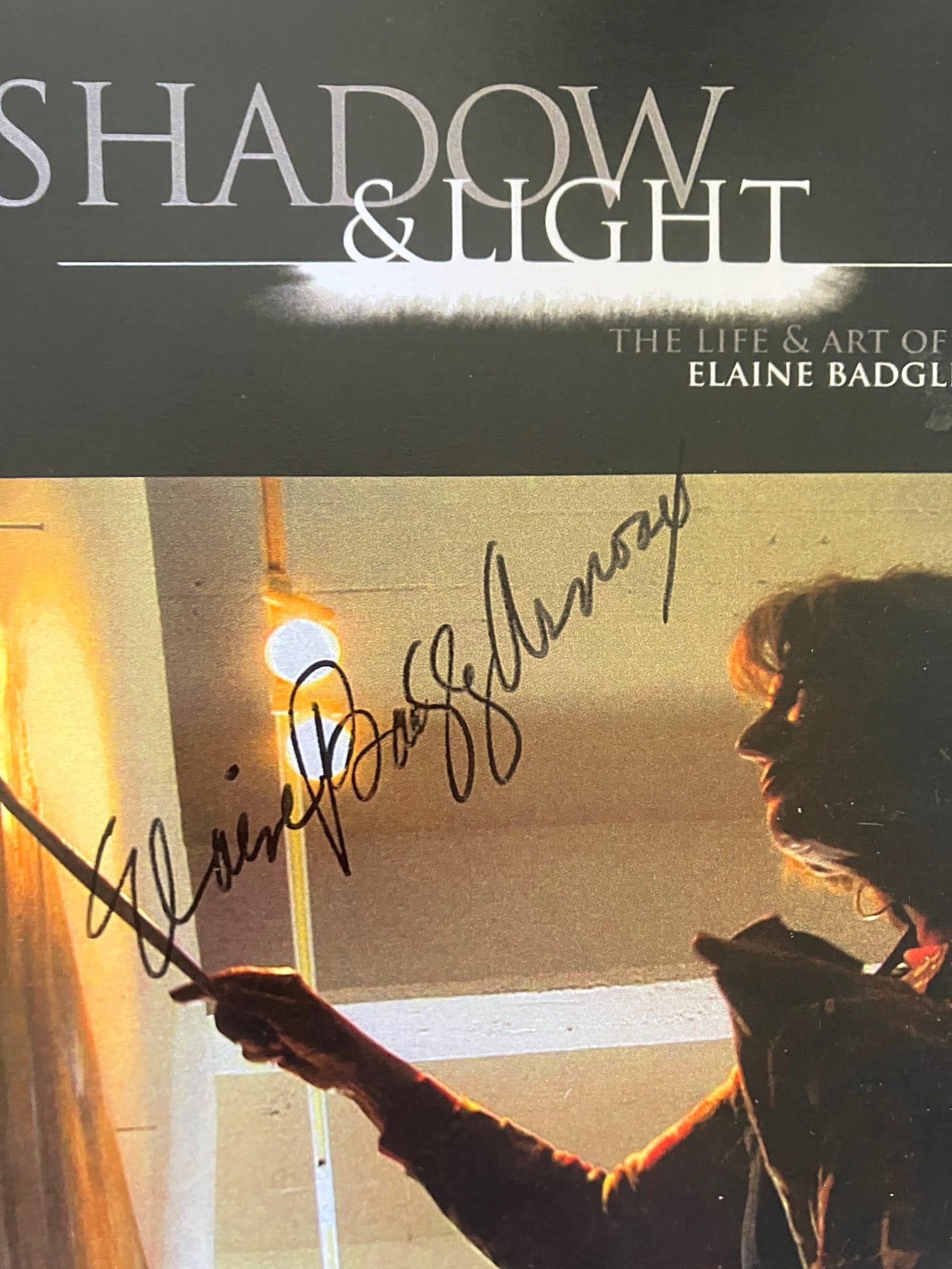

A year went by. I had finished Shadow and Light, the film about the painter Elaine Badgley Arnoux, and it was making its rounds on the film festival circuit. Yet, Harold’s terrible war stories kept creeping back into my mind. They were dramatic, and the violence he described was far beyond what my sensibilities could comfortably handle. I couldn’t imagine how I could possibly turn this material into a movie. I mentioned Harold’s stories to a friend, who said, “Don’t you think you should see what else he has to say?” I contacted Elaine and asked if she thought Harold would be interested in telling his war stories on camera. She replied, “He has been waiting his whole life to tell his war stories on camera.” I filmed an interview with Harold, only to discover that his new stories were even more disturbing than the earlier ones. What he had done in combat was shocking—a nightmare recounted with undiminished rage toward the Nazi enemy of his vivid memory. I put Harold’s interview material away, certain I was not interested in making a horror movie.

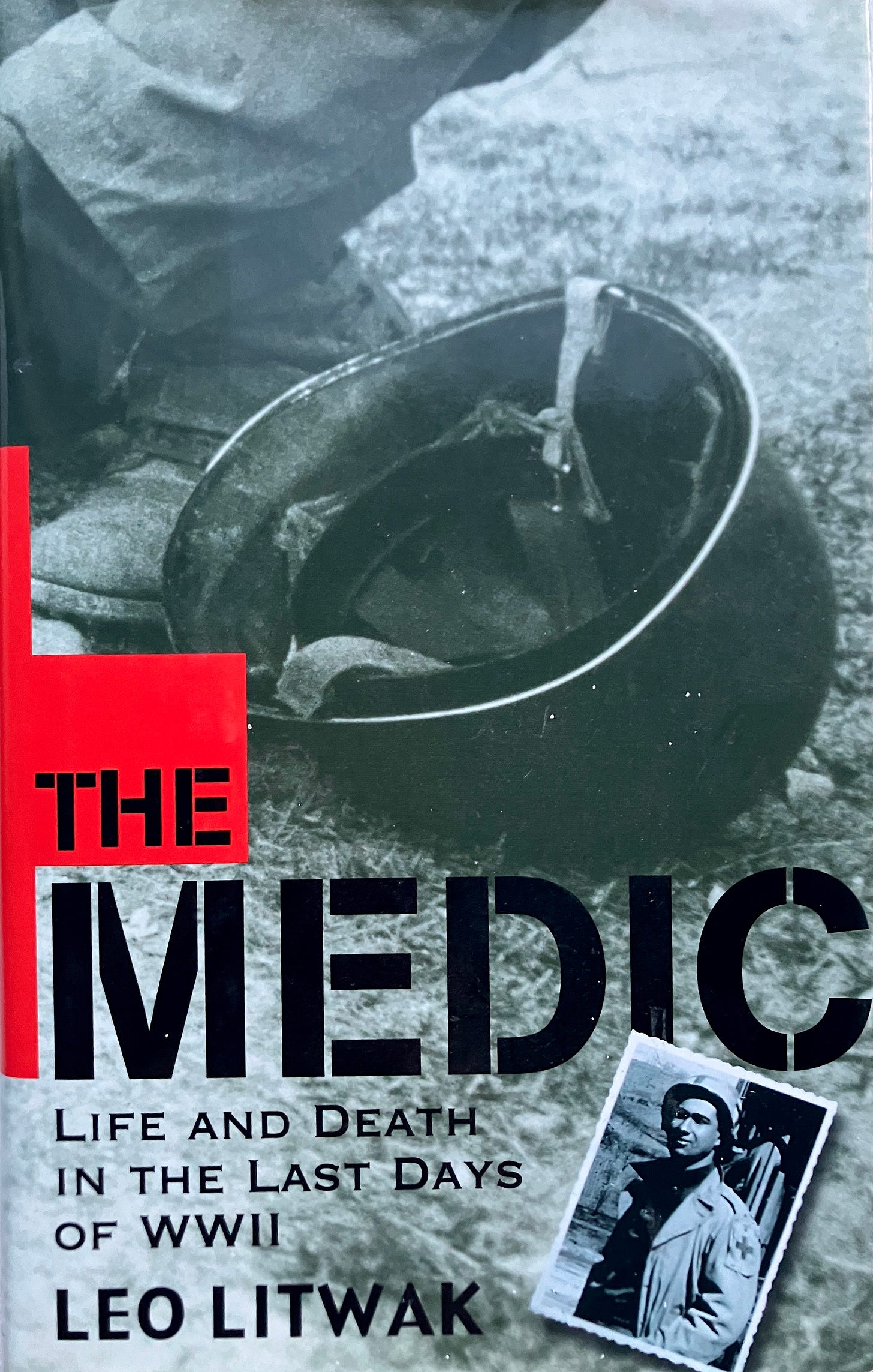

Time passed, as it often does. I pursued other creative projects. One night, after leaving a film screening, I ran into the novelist Herbert Gold. He had appeared in a documentary I made with Mal and Sandra Sharpe called The Old Spaghetti Factory, which was about the last Bohemian café in San Francisco. Herb remembered me from the film and suggested that we should go to some movies together. I agreed to give it a try. His childhood friend, Leo Litwak—a writer and professor at SFSU—joined us for many lunches. Herb mentioned that Leo had written a book about his experiences as a medic in World War II. By then, I had dismissed the idea of making a documentary about war months earlier. But as a gesture of friendship with Herb, I asked Leo if he would be interested in being interviewed about his time as a medic. He agreed.

Leo Litwak was a quiet, unassuming man and a brilliant raconteur. With his non-judgmental attitude, he explained that most German soldiers were conscripted into service and were not necessarily Nazi sympathizers. His perspective offered a completely different take on Germans—the so-called enemy. It was a hundred and eighty degrees opposite from Harold Kozloff’s rage. Maybe, just maybe, I had stumbled into the makings of a movie.

At the annual Ideas in Motion Christmas party, fellow filmmaker Jim Mayer told me I should meet his neighbor, Paul Mico, a World War II veteran who had been sharing his combat experiences with him. We all met for lunch, and Paul proved to be a very good storyteller. His stories covered a wide range of experiences, from heroic acts to actions that still haunted him. His candor was disarming, and his sincerity shone through in his voice.

It was my great good fortune to find three men who represented the emotional complexities of being in combat: anger, empathy, and sorrow.

Here’s the trailer for I Wanted To Be A Man With A Gun, three American soldiers in WWII.

William Farley©2025

A real experience of a war that can haunt. A LOT TO LEARN HERE! Great moviemaking Farley.